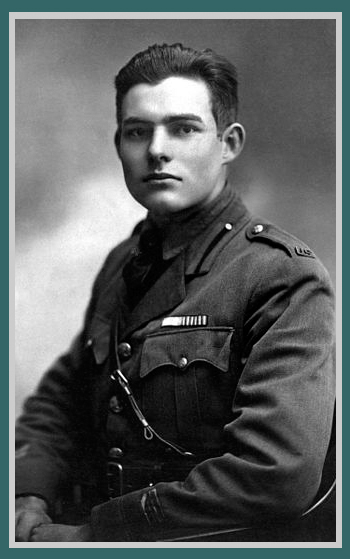

Young Hemingway's Wound and Conversion

By Matthew Nickel - Highland, New York, USA - 1 March 2013

The immense majority has faith in human wisdom and good sense, faith in the doctrine of human perfectibility. . . . As for what we generally understand by beliefs, ancient mores, ancient traditions, the power of memories, I have not seen any trace of these up to now. I even doubt that religious opinions have as great a power as one thinks at first sight. The state of religion among this people is perhaps the most curious thing to examine here (Alexis de Tocqueville to Louis de Kergorlay, 1831).

Until the young Ernest Hemingway arrived in Europe to serve as an ambulance driver with the Red Cross, he had never been exposed to the “ancient mores” and “ancient traditions” Alexis de Tocqueville found absent throughout the American landscape. This does not mean that Hemingway might not have been exposed to any traditions, but the American experience was democratic in nature and relatively new compared to the old world. The contrast of the medieval aesthetics and traditions the Catholic Church had imprinted throughout most of Europe with the Protestant American midwest Hemingway was raised in would be striking to a young man who had grown up in an affluent Chicago suburb, who had sung in the Congregational Church choir, who had participated in church youth programs, and whose parents did not keep a liquor cabinet. The consequences would also be cumulative and lifelong, inspiring new pilgrimages, demanding a deeper engagement with history, place, and the rituals of those ancient mores and traditions. What he took from Europe, he brought with him to make new in places like Key West, Cuba, Wyoming, Montana, and Africa, but Catholicism would always be near the center of his life. Though decades of critics would see Hemingway’s world rooted in a rubric of abandonment, disbelief, or despair, his quest for an understanding of his faith and his struggle within that faith is a story about the human heart’s struggle, through failure and success, with matters of the spirit.

Until the young Ernest Hemingway arrived in Europe to serve as an ambulance driver with the Red Cross, he had never been exposed to the “ancient mores” and “ancient traditions” Alexis de Tocqueville found absent throughout the American landscape. This does not mean that Hemingway might not have been exposed to any traditions, but the American experience was democratic in nature and relatively new compared to the old world. The contrast of the medieval aesthetics and traditions the Catholic Church had imprinted throughout most of Europe with the Protestant American midwest Hemingway was raised in would be striking to a young man who had grown up in an affluent Chicago suburb, who had sung in the Congregational Church choir, who had participated in church youth programs, and whose parents did not keep a liquor cabinet. The consequences would also be cumulative and lifelong, inspiring new pilgrimages, demanding a deeper engagement with history, place, and the rituals of those ancient mores and traditions. What he took from Europe, he brought with him to make new in places like Key West, Cuba, Wyoming, Montana, and Africa, but Catholicism would always be near the center of his life. Though decades of critics would see Hemingway’s world rooted in a rubric of abandonment, disbelief, or despair, his quest for an understanding of his faith and his struggle within that faith is a story about the human heart’s struggle, through failure and success, with matters of the spirit.

In a letter to his mother, Grace, on 16 January 1918, Ernest Hemingway, then eighteen years old, wrote from Kansas City attempting to alleviate his mother’s anxiety about the condition of his soul: “Don’t worry or cry or fret about my not being a good Christian. I am just as much as ever and pray every night and believe just as hard so cheer up! Just because I’m a cheerful Christian ought not to bother you.” Hemingway continued, justifying how he did not “rave about religion” but was “as sincere a Christian” as he could be. He explained he had not recently been to church because Sunday was the one day he got sleep during the week (he had just joined the Missouri Home Guard) and because “Aunt Arabell’s church is a very well dressed stylish one with a not to be loved preacher.” Hemingway handled his mother’s sentimental piety tactfully, even if her judgment of his friends Bill Smith and Carl Edgar made Hemingway “awfully angry.” After assuring her that he had not abandoned his Christian beliefs, he asserted his own independence, his ability to have friends that also believed in “God and Jesus Christ” and had “hopes for a hereafter,” and his desire to have “deep sincere Christian” friends as opposed to those who “drool at the mouth like a Peaslee with religion.” Finally, he pointed out that he had never asked Bill what church he went to, because “creeds don’t matter” (Selected Letters, 2003, 3-4).

This letter to his mother was written six months before Hemingway was wounded at Fossalta on the Italian front in World War I. Hemingway had already been thinking about and living his life according to his own unique perspective before Italy. From the letter, we learn how he believed his cheerfulness as a Christian (as opposed to morbidity or sentimentality), should have been sufficient to still call himself a Christian; he preferred not to “rave” about his religion; he would rather have avoided “well dressed stylish” churches with unlikeable preachers; he valued a sincere Christian who did not “drool at the mouth...with religion”; and he believed “creeds” matter less than actions, sincerity, and being “a gentleman” (Ibid). This perspective would be in evidence throughout much of his writing: action signified more than mere words or good intentions; talking too much about anything was to be avoided. As he wrote in The Nick Adams Stories, “That was what had made the war unreal. Too much talking. Talking about anything was bad.... It always killed it” (237). His writing and his exemplary characters avoided what Ezra Pound called “emotional slither.” Hemingway also consistently turned from showiness or ornateness: “Prose is architecture, not interior decoration, and the Baroque is over” (Death in the Afternoon, 191).

By the time Hemingway was eighteen, he was consciously rejecting his mother’s insistent piety. The experience of World War I likely confirmed for Hemingway how Oak Park liberal theology and his mother’s expectations of a Christian man would not suffice in the face of mechanized warfare, bloodshed, and violence. The sentimentality Hemingway experienced before leaving home resembled in many ways what Flannery O’Connor describes in Mystery and Manners as “an excess, a distortion of sentiment usually in the direction of an overemphasis on innocence” (147). In his early fiction, Hemingway responded critically to what Larry Grimes calls “the official theology of Oak Park Congregationalism,” in which “evil, disorder, and the force of the irrational” were unacknowledged. Certain characters in his stories echo this sentimental piety; Hemingway’s rejection of this “overemphasis on innocence” was pervasive.

Soldiers’ stories in Europe, the dead swollen in the sun -- whom Hemingway moved from the explosion of a munition factory outside Milan -- the noise of machine gun fire, trench mortar, and the experience of being blown up, would reveal to the young man a far different reality than that of his childhood. This war experience, and Hemingway’s wound, have been discussed at length throughout several biographies, but James Nagel’s Hemingway in Love and War (1989) succinctly revises the erroneous assumptions of some accounts, such as the claims he actually served in the army, while revealing important details about Hemingway’s World War I experience. Hemingway had served as an ambulance driver at Schio for two weeks, and then with a canteen unit on the Piave River. Within six days of joining the unit, on July 8, 1918, he was wounded with a mortar shot to the right foot and knee. Soon after he his release from the hospital in October, he returned to the front, limping and using a cane, for only one day, at which point he contracted hepatitis and returned to the hospital in Milan” (Nagel and Villard, 1989, 252-53). Nagel presents strong evidence that Hemingway was not only wounded by 227 pieces of shrapnel from a trench mortar explosion, but also that he was struck by machine gun fire.

While accuracy is always important, especially given the mythic variations Hemingway and others concocted from what might have happened on the battlefield, the central fact is that the young man was injured at the age of eighteen very far from home and far from the shelter of any liberal theology. Indeed, it is hard to conceive how a certain form of American Protestantism, described by Alexis de Tocqueville in the nineteenth century as largely composed of a general “faith in human wisdom and good sense, faith in the doctrine of human perfectibility,” could have helped Hemingway deal with the experience of World War I.

Though Nagel’s study is indispensable, he underestimates the trauma the wound may have caused by dismissing any possibility that Hemingway may have experienced what would have been called shell-shock in World War I or post-traumatic-stress-disorder (PTSD) decades later. Because Hemingway did not display evidence of being shell-shocked in his letters written from the hospital and because Henry Villard, his hospital room neighbor, and his nurse Agnes von Kurowsky, saw no sign of PTSD, Nagel concludes that Hemingway later exaggerated or fictionalized what really happened to him psychologically. However, contrary to Nagel’s conclusions, several decades worth of studies since World War I do show how the effects of war trauma often do not surface in the individual until several months or even years after the initial experience.

In her Smithsonian article, “The Shock of War” (2010), Caroline Alexander points out the difficulty and almost impossibility doctors experienced in diagnosing shell-shock in World War I, for “it was precisely the soldier’s ability ‘to carry on’ that had aroused skepticism over the real nature of his malady” (6). In addition, Alexander defines traumatic brain injury (TBI), a syndrome that appears like PTSD, but which differs in that TBI “may manifest no overt evidence of trauma -- the patient may not even be aware an injury has been sustained. Diagnosis of TBI is additionally vexed by the clinical features -- difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbances, altered moods” (7). Both syndromes are difficult to detect, and both were extremely common in soldiers who were wounded or who were near intense explosions. While it is impossible to determine exactly what young Hemingway experienced, the possibility that it was shell-shock or a traumatic brain injury is very plausible. Many of Hemingway’s characters in his fiction deal with the after-effects of severe wounds, often received in battle, and the spiritual progression of several characters, most notably Frederic Henry and Colonel Cantwell, is caught up with the effects of war and the ability of each character to reconcile with the facts of trauma and survival.

In an article in The Hemingway Review, “Hemingway’s Out of Body Experience” (1983), Allen Josephs identifies “the transcendent psychic phenomenon known as an Out of Body Experience (OBE)” as something else Hemingway may have lived through when he was wounded (11). Josephs first analyzes the biographical record and the way Hemingway described his wounding experience to others. For instance, Hemingway explained in a letter to Guy Hickok how he felt his “soul or something coming right out of [his] body, like you’d pull a silk handkerchief out of a pocket by one corner. It flew around and then came back and went in again and I wasn’t dead anymore.” In addition, Josephs also examines Hemingway’s fictional scenes (especially in “Now I Lay Me” and A Farewell to Arms) where his characters describe what may seem to be an out of body experience, and he presents persuasive evidence that Hemingway may have experienced an OBE. He concludes that his wounding was not so much a “crippling or ‘fixating’ trauma” as might have occurred if he were merely shell-shocked, but that it was “the beginning of a possibly transcendental journey.” Several studies done on OBE find the most common effect is for the sufferer to become convinced he has a soul or non-physical self that will survive the body at death.

Because it is impossible to know exactly what Hemingway experienced, it is probably best to leave open the possibility that he was affected with something like shell-shock from the explosion and that the wound or shock itself may have caused an OBE. Given the way Hemingway discussed the matter of his wound with Hickok and Hemingway’s employment of the word “soul” in the letter, and also in “Now I Lay Me,” and in the manuscript for A Farewell to Arms, it is possible one of the most important realizations Hemingway gained from his wound was the existence of his soul. The fact that a Roman Catholic priest may have performed the rite of extreme unction over Hemingway’s wounded body may have added power to this recognition, for Hemingway had already been seeking something more than the theology of his childhood when this encounter with a priest occurred.

The priest appeared at a ripe moment for Hemingway, whether he was dying or not, and the wounding experience -- the feeling that he had lost his soul and that it had come back, the very recognition of his soul -- and the ritual performed by the priest which affirmed the sanctity of the soul and its eternal destiny, sparked an intense yearning for something that might also affirm the sanctity of transient flesh.

Critics such as Killinger, Donaldson, Waldmeir, and others who find in Hemingway some philosophy of man, some identification with a nothingness or despair in a God-less world as corollary to his wounding experience, miss the point. If Hemingway realized he had a soul, it makes little sense that he would abandon belief in anything spiritual for a creed of nothingness or despair. Larry Grimes identifies one key factor in the religious design of Hemingway’s fiction as “Hemingway’s descent into darkness and the discoveries consequent to that descent,” but this descent is not representative of, as Grimes claims, “the horrible nothingness of life in a world where religion, in the premodern sense of the word, does not exist.” It is a recognition and acceptance of a darkness, or what some call original sin, that is pre-requisite to finding absolution.

Though many biographers believe Hemingway was a nominal Catholic only after he became interested in the devoutly Catholic Pauline in 1925, biographical evidence indicates that Hemingway was interested in, learning about, and practicing the rituals of Catholicism shortly after World War I. A letter Hemingway wrote to Grace Quinlan on September 20, 1920, indicates that Hemingway wrote to Grace Quinlan about entering into a Catholic church in Petoskey with Kate Smith, and lighting candles and praying there. At the end of the letter, Hemingway added: “P.S. Burned a candle for you. Wonder if you’ll rate any results. Told ’em to give you whatever you want” (Letters I, 2011, 244-245). Hemingway’s biographer Kenneth Lynn claims that Hemingway’s conversion in 1918 by the priest in the dressing station was “the stuff of which myths of war trauma are made” and that “there is no persuasive evidence that he ever knelt in prayer in a church that was not Protestant until the day he and Katy lit the candles in Petoskey” (123). However, Lynn’s criticism glosses over the not insignificant fact that Hemingway had only been home two years since the war before he was bringing someone else into a Catholic church and praying with them.

But this was not the only time Hemingway demonstrated an interest in the Catholic Church before Pauline. In 1921, when he was courting his first wife Hadley Richardson, Hemingway “asked her if she would pray with him in the Milan cathedral as Agnes would not.” Who is to say Hemingway did not go in and pray himself, for it is known he went in and was moved by both the Duomo in Milan -- Hemingway described it “Like a great forest inside” -- and Notre Dame de Paris, which he preferred. In addition, Morris Buske, in the “Hemingway Faces God” in The Hemingway Review (2002), reveals unpublished notes from Hemingway’s sister Marcelline Hemingway Sanford, for her memoir At the Hemingways, in which she explained that her brother “had joined the Catholic Church before his marriage to Pauline.”

Furthermore, there is sufficient evidence in the published correspondence to indicate Hemingway’s interest in and practice of Catholicism. In his article, Stoneback has listed key published and unpublished letters pertinent to religion, religious subjects, and Christian writers. One of the best examples is Hemingway’s letter to Ezra Pound dated July 19, 1924, from Burguete, almost a year before he met Pauline. In it, Hemingway revealed his devotion at the Fiesta of San Fermín in Pamplona, Spain. As he wrote to Pound: “I prayed to St. Fermin for you. Not that you needed it but I found myself in Mass with nothing to do and so prayed for my kid, for Hadley, for myself and your concert” (Selected Letters, 119). This confession of prayer for Pound in a famously Catholic town -- during a devoutly Catholic fiesta on a significant religious pilgrimage route -- is not insignificant.

One of the most important early statements by Hemingway is in a letter to Ernest Walsh, dated January 2, 1926, wherein he referred to himself explicitly as a Catholic and to the “extreme unction” given to him on the battlefield. Hemingway wrote: “If I am anything I am a Catholic. Had extreme unction administered to me as such in July 1918 and recovered. So guess I am a super-catholic.... Am not what is called a ‘good’ catholic.... But cannot imagine taking any other religion seriously.” It is impossible to know exactly what occurred on the battlefield between Hemingway and the priest, but regardless, there is ample evidence that Hemingway practiced Catholic rituals and that he talked and wrote to others about being a Catholic after World War I. Also, the results of a canonical inquest into Hemingway’s standing in the Catholic Church by the Archdiocese of Paris – which on April 25, 1927 reported he was “certified a Catholic in good standing” -- are telling.

What is also clear from the biographical record is Hemingway’s increasing restlessness with Oak Park and his parents after coming home from the war. In The Young Hemingway, Reynolds points out how Hemingway continually “wanted his father to assert himself under his own roof” (102), how he “found it more and more difficult to speak honestly with his father, whose stern morality would not bend and whose Christian forgiveness Ernest found self-serving and difficult to accept” (128), and how he “chaffed under his mother’s moralizing proverbs” (128). Furthermore, Buske maintains that Hemingway may have found significant paternal solace in his new-found religion: “Catholicism offered Hemingway an alternative to his father’s failures as well. While kneeling at Mass or at Confession, contrite, he could receive through a Father the promise not of swift punishment but of absolution and redemption” (85).

In the summer of 1920, Hemingway’s relationship with his mother reached a climactic point when she kicked him out of their cottage Windmere “for insolence and idleness.” Her subsequent letter to him exemplifies everything Hemingway hated about her self-righteousness. Her accusations may have been accurate and arguably justifiable, but her tone would have been insulting to a war-wounded young man. She wrote to him describing how “the Mother is practically a body slave to [her young child’s] every whim” and explaining the way “a mother’s love seems to me like a bank.... There are no deposits in the bank account during all the early years,” and when the child becomes a man, “the bank is still paying out love, sympathy with wrongs, and enthusiasm for all ventures; courtesies and entertainment of friends who have nothing in common with the mother, who, unless they are well bred, scarcely notice her existence.” Her tone was self-pitying, sentimental, pious, and guilt-ridden, and she continued listing all the things a son could do to make “a few of the deposits which keep the account in good standing,” like praising her cooking, showing an interest in hearing her sing, giving gifts of flowers for her birthday:

Unless you, my son, Ernest, come to yourself, cease your lazy loafing, and pleasure seeking -- borrowing with no thought of returning -- stop trying to graft a living off anybody and everybody...and neglecting your duties to God and your Savior Jesus Christ -- unless, in other words, you come into your manhood -- there is nothing before you but bankruptcy: You have over drawn (Reynolds, 1986, 136-38).

His mother’s letter was enough; Ernest left Oak Park for good.

Hemingway moved to Chicago the following October. While dealing with the after-effects of the war and his wound, his early attempts at poetry indicated some of the things Hemingway was trying to reconcile about his experience. For instance, in Chicago in 1921, Hemingway wrote a poem, “Killed Piave -- July 8 -- 1918,” a title suggestive enough:

Desire and

All the sweet pulsing aches

And gentle hurtings

That were you,

Are gone into the sullen dark.

Readers might wonder to whom the poem was addressed. It seems this first “you” was himself or his former youth. The poem continues:

Now in the night you come unsmiling

To lie with me

A dull, cold, rigid bayonet

On my hot-swollen, throbbing soul.

The second “you” is a far darker presence, possibly death, maybe in the form of a mistress, and strikingly resonant with images from the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. Another poem written in Chicago, 1921, uses similar Baudelairean night and dark imagery:

Cover my eyes with your pinions

Dark bird of night...

Dip with your beak to my lips

But cover my eyes with your pinions.

This was amateur poetry at best, but indicative of Hemingway’s struggle for some light in the dark night.

It is likely Hemingway was reading Baudelaire within the years after the war (certainly when he lived in Paris), just as it is known he was reading the poetry of François Villon. Both poets were highly influential in twentieth century literary modernism, and both exhibited an “insistence on a vision of evil (or Original Sin) that leads to the recognition of grace.” (Stoneback, The Sun Also Rises, 309). In The Poetry of Villon and Baudelaire, Robert R. Daniel defines both as poets who “face suffering and death and dwell on the horrors that await all human flesh after death,” but also believers who “envision a transcendent state which they hope to attain by three means: poetry, prayer and death” (8). Given his wound and the difficulty afterward Hemingway experienced sleeping in the night, his continual yearning for a light in darkness, Baudelaire and Villon would have provided for him the necessary mixture of poetry and prayer to deal with death, sin, and redemption.

Shortly after marrying Hadley in September 1921, Hemingway sailed to Paris with his bride. In Europe, Hemingway experienced a different kind of piety from the one he had been raised in, one that would remind him of Italy “where men could make jokes about [their religion] without giving it up” (Reynolds, 1999, 346). With his increasing interest in “all things medieval” (346), Europe was the perfect place to learn about and experience the ancient traditions of the Church first hand.

It has long been documented how Hemingway was influenced in Paris by certain avant garde writers of the Left Bank, and how he quickly became friends with figures like Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. Often unsaid is how Hemingway entered Paris at a time when there was a profound Catholic revival among French and English intellectuals. These writers included Jacques Maritain, Paul Claudel, and G. K. Chesterton -- those who, through a revival of Saint Thomas Aquinas’ theological methodology, formed a large part of the Catholic renouveau. Given Hemingway’s interest in Catholicism after the war, he would have known these writers, if not personally, at least through their work and their strong presence in modernism. Stoneback makes a strong case for Hemingway’s consciousness of Claudel as he wrote The Sun Also Rises, and it is clear from his unpublished letters in the 1950s that Hemingway knew of Claudel and had been reading his correspondence with André Gide (see especially letters to Adriana Ivancich and Bernard Berenson). Hemingway would have heard of these French writers (Maritain, Claudel, and their other compatriots Jean Cocteau and André Gide), through his first important mentor and life-long friend Ezra Pound. Pound knew many of them and had been writing reviews of their work as early as 1913 in Poetry: A Magazine of Verse and The New Age. Those first few months in Paris were crucial in Hemingway’s apprenticeship as he dove deep into a literary renaissance, listening and reading as much as he could, especially Pound, thirsting for knowledge about writing, modern writers, and artists, and he would have been exposed, as a journalist and around Parisian literati, to numerous important Catholic writers connected with La Nouvelle Revue Française and Action Française.

During the composition of The Sun Also Rises in 1925, Hemingway examined several writers -- some of whom were a part of this Catholic revival -- in an unpublished short essay titled “On Cathedrals.” In the essay, presumably written in Chartres, Hemingway discussed cathedrals, and he criticized a handful of writers who had attempted to write about cathedrals, particularly the “Catholic journalism” of Hilaire Belloc and the “fancy writing” of “that sloppy brained convert Huysmanns [sic]” (Stoneback, The Sun Also Rises, 306). Hemingway’s avoidance of what he considered Belloc’s “Catholic journalism” and J. K. Huysmans’ decadent form of mysticism (seeing decadence as a Roman Catholic rebellion against materialism) was at the heart of his vision of the iceberg and his desire to avoid any spiritual slither that might deaden “the glory of an object” like the great Cathedral at Chartres. Instead, Hemingway would likely have preferred the Catholicism of a writer like Paul Claudel, whose “understated mysticism” was “more congenial than the work of a Huysmans or Belloc” (Ibid, 307).

Given Hemingway’s profound friendship with Ezra Pound, the possibility that he was exposed to the writing of T. E. Hulme, Pound’s old friend who had died in World War I, also seems likely. For instance, he would have read Hulme’s early Imagist poetry included in Pound’s Ripostes (1912) and in Umbra (1920), where Pound published “Poem: Abbreviated from the Conversation of Mr. T. E. H.” (According to Hemingway’s Library, Hemingway owned at least thirty books by Pound, including Umbra). Considering the poetry Hemingway was writing in Chicago, he might have paid particular attention to Hulme’s account (transcribed or written by Pound) of the French front in World War I in “Poem,” which juxtaposes the trenches at St. Eloi, sandbags, and “Night,” with men walking back and forth, “pottering over small fires, cleaning their mess-tins: / To and fro, from the lines” where they wander between dead horses and a “dead Belgian’s belly” (Pound, New Selected Poems and Translations, 52). The last two lines are strikingly resonant of shell-shock and the “nothing” Hemingway would soon come to write about: “My mind is a corridor. The minds about me are corridors. / Nothing suggests itself. There is nothing to do but keep on” (125).

After the alleged conversation that led to “Poem,” Hulme returned to the war and died in 1917 at Oostduinkerke near Nieuwpoort, in West Flanders. Hulme’s writing was very influential during and after World War I. Ronald Schuchard argues that Hulme’s influence on T. S. Eliot predicated Eliot’s famous classicist sensibility. Hulme’s writing, especially on the doctrine of original sin in an essay, “Romanticism and Classicism,” was foundational in establishing the differentiation between Rousseau’s romanticism that rejects original sin and a classicism that accepts it. Hulme’s clarification of the classical view was a major tenet of the Catholic renaissance in France and England, and Hulme’s definition of Rousseauean romanticism contains many similarities to Oak Park’s liberal theology.

The classical foundation of Imagism was in many ways also influenced by the classical revival among intellectuals like Hulme. As an original Imagist, Hulme’s rejection of romanticism was carried over into poetry, and the classical ideal morphed into Pound’s famous definition of an image: “Direct treatment of the ‘thing’ whether subjective or objective”; “To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation”; “As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of the metronome” (Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, 3). Scholars have long analyzed Pound’s Imagist principles in Hemingway’s work, but rarely has anyone considered Hemingway’s rejection of Oak Park Congregationalism and his yearning toward a Catholic vision as a parallel to Hulme’s rejection of Rousseauean romanticism and acceptance of the doctrine of original sin.

In “Romanticism and Classicism,” Hulme clarified the definition of romanticism as derived from Rousseau:

They had been taught by Rousseau that man was by nature good, that it was only bad laws and customs that had suppressed him. Remove all these and the infinite possibilities of man would have a chance.... Here is the root of all romanticism: that man, the individual, is an infinite reservoir of possibilities; and if you can so rearrange society by the destruction of oppressive order then these possibilities will have a chance and you will get Progress (116).

He identified the classical view as the opposite of the romantic, that “Man is an extraordinarily fixed and limited animal,” and “it is only by tradition and organisation that anything decent can be got out of him.” Furthermore, Hulme pointed out how the Church had always, since the fifth century Pelagian Heresy, accepted “the adoption of the sane classical dogma of original sin.” Thus, for Hulme (and Maurras, et al.), Rousseau’s romanticism rejected the doctrine of original sin, and Hulme saw the only redemption from nineteenth century romanticism and scientific positivism (what Hulme sees as the offspring of romanticism) in the classicism that accepted original sin.

Hemingway’s rejection of the Oak Park sensibility, Victorian morality (that had recently made law the prohibition of alcohol), the belief in the perfectibility of man, and the social gospel, would have led him straight to the type of classicism and the doctrine of original sin espoused by Hulme and other Catholic figures in Paris in the 1920s. Hulme further defined man as “endowed with Original Sin. While he can occasionally accomplish acts which partake of perfection, he can never himself be perfect.” This is not to say that Hemingway was a classicist in the Charles Maurras-Hulme sense, but he did value the doctrine of original sin à laBaudelaire, and his main characters, particularly Jake Barnes, Frederic Henry, Robert Jordan, and Colonel Cantwell all seek some form of redemption. Atonement is at the heart of many Hemingway stories, a testimony to a recognition of the imperfectibility of mankind.

Given Hulme’s identification of classicism with certain controversial political figures like George Sorel, Charles Maurras, and Pierre Lasserre, those once a part of Action Française, Hemingway, who often sought to remain apolitical, anti-communist and anti-fascist, naturally would have distanced himself from association with such a group. Still, Hemingway’s interest in Catholicism, his affinity for “all things medieval,” and his continuing education about the war, would have led him to this resurgence of Catholicism after World War I. He would have paid particular attention to the way these writers radically returned to Catholic tradition, finding it compatible with modernism through mysticism. And he would have been aware of one of their most important nineteenth century influences: Charles Baudelaire.

The classical reaction against romanticism. in combination with a renewed interest in mysticism and “la mystique,” opened the way for a writer like Jacques Maritain, who wedded antiquity and the avant garde through a revived interest in Aquinas and the deep influence of Baudelaire. Robert Daniel explains how “Despite his insistence on modernity in his critical writings, Baudelaire was enthralled by the past and sympathetic to elements of the medieval world view.” Stephen Schloesser in Jazz Age Catholicism (2005), succinctly documents Baudelaire’s presence in Maritain’s philosophy, and we might consider Baudelaire’s presence in Hemingway’s Catholic aesthetic in a similar manner:

Baudelaire’s solution of the problem of “modernity” famously defined beauty as being “always and inevitably of a double composition...made up of an eternal, invariable element, whose quantity it is excessively difficult to determine, and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you like, whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions.” Baudelaire amplified the terms: “By ‘modernity,’ I mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable”...

“By neglecting it, you cannot fail to tumble into the abyss of an abstract indeterminate beauty” (166).

Schloesser describes the World War I French Catholic generation as a “realist generation” with “a twist, in this case, a synthesis of realism and ‘mysticism’ -- a catch-all term that included supernaturalism, miracles, and the mysterious, as well as personal spirituality and orthodox religion” (117).

Hemingway’s Catholic and artistic vision contained many of the same philosophical and theological principles these other Catholic intellectuals supported. For instance, his affinity for the cathedral at Chartres, Saint Louis IX, the medieval town of Aigues-Mortes, Roland and Roncevaux, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, apparitions of the Virgin Mary, Mont-St.-Michel, and many other medieval figures and places exemplify the way Hemingway also wedded antiquity and the avant garde. His exemplary characters, after a profound recognition of original sin, always seek reconciliation with imperfection, yearning toward repentance through a form of traditional rituals: Jake Barnes acknowledges his wound and still prays, attends Mass, processions, and confession; Frederic Henry suffers the dark night while learning from the priest how to pray, how he may become very devout; Robert Jordan learns slowly and then all at once in that moment of conversion through la gloria, which ultimately leads to his sacrifice; and Santiago, the old fisherman, promises to say ten Hail Marys, ten Our Fathers, and to make a pilgrimage to the Virgin of Cobre if he catches the marlin. Hemingway’s interest in the poetry of Baudelaire and Villon paralleled his resistance of ennui through his quest to identify the sacred in ordinary moments of communion between friends, with wine and spirits and good meals, before the dark mystery returned in the night. And finally, the most mystical moments in Hemingway’s fiction are seen in ordered and disciplined action, which reveal the presence of mystery and actual grace in rituals like the bullfight, and sports like bicycle racing, hunting, fishing – in the act, like the great faena of the torero, “that takes a man out of himself and makes him feel immortal while it is proceeding, that gives him an ecstasy, that is, while momentary, as profound as any religious ecstasy; moving all the people in the ring together and increasing in emotional intensity as it proceeds” (Death in the Afternoon, 206-207).

Hemingway’s life would lead him on a continual quest for sacramentals, and Catholicism offered a confirmation of the sanctity of the world he lived in. His rejection of his parents’ piety was a rejection of sentimentality, of excess, of an over-emphasis on innocence, and the possibility that any man or woman can be perfect on earth. His rejection, evident in the above quoted letter to his mother from before the war, was theologically Catholic before he even encountered Catholicism. His characters and his stories attest to another piety, that which accepts the presence of sin and certain rituals of atonement, that which acknowledges imperfection while seeking, through grace, a joy in earthly objects as reflective of the heavenly good. This piety is contained in the image of Jesus and His compassion and mercy, His self-sacrifice for the salvation of humanity from sin. Or it can be found in the image of the pietà central to Christian mystery: the Blessed Virgin Mother holding her dead child Christ, an image which is at once a reminder of mankind’s imperfection through the death of Christ, our participation in his crucifixion, as it points toward a resurrection, an ultimate redemption.

Nota bene: This text is excerpted and adapted from the first chapter of Mr. Nickel’s new book, Hemingway’s Dark Night: Catholic Influences and Intertextualities in the Work of Ernest Hemingway (2013), newly published by New Street Communications in Wickford, Rhode Island. More information may be found at www.newstreetcommunications.com.