Waugh and Wall-E

By Christopher Killheffer - New Haven, Connecticut, USA - Ordinary Time/All Saints 2011

Recently I had the unusual opportunity to experience two dystopias in a single evening. I was traveling, and with Evelyn Waugh’s Complete Stories along for the train ride, had come upon his "Love Among the Ruins" for the final leg of the trip. Hardly three hours after finishing with that vision of future grimness, I turned on my hotel television to catch the beginning of Wall-E, the 2008 animated film which is, like Waugh’s story, a vision of calamity to come. Captivated, I watched through to the end, and so went to sleep with the dystopias of Waugh and Wall-E juxtaposed in my mind.

What was remarkable about that juxtaposition is not how different the two visions are; you could hardly expect much similarity between the Catholic, quasi-aristocrat, mid-century Waugh and the 21st century Pixar studio. What is remarkable is how the two views, despite their immensely different sources and emphases, tend to complement and even correct one another. Dystopias are meant to trace a trajectory, to reveal something about our present condition by indicating, usually through exaggeration, where that condition leads. The trajectories traced by Waugh and Wall-E are so dissimilar they seem to have no meeting point, two lines that never intersect. But if we hold them side by side, we find that their parallel lines of sight, like those of our eyes, form a vision that is richer and truer for being taken together.

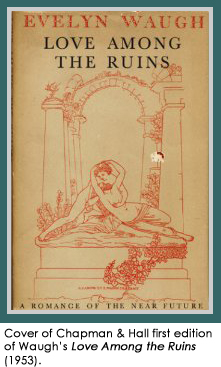

"Love Among the Ruins" is, as its subtitle proclaims, "a romance of the near-future," taking place perhaps thirty forty years after 1953, when it was written. Waugh does not bother trying to envision changes in technology; his concern is entirely with the character of society and the power of the state. Lacking the obvious menace of 1984's Big Brother, the state in Waugh's story is nevertheless similar to Orwell's in its ambition to control every aspect of life: censoring the arts, banishing religion, assigning jobs and spouses, even trying (in vain) to manipulate the weather. Much of its meddling appears in forms that are recognizable as exaggerations of long-standing conservative fears about big government: violent criminals are treated to luxurious rehabilitation in fine country homes; young people are subjected to sterilization; euthanasia centers are mobbed by throngs of the "welfare-weary" who daily present themselves for voluntary annihilation.

"Love Among the Ruins" is, as its subtitle proclaims, "a romance of the near-future," taking place perhaps thirty forty years after 1953, when it was written. Waugh does not bother trying to envision changes in technology; his concern is entirely with the character of society and the power of the state. Lacking the obvious menace of 1984's Big Brother, the state in Waugh's story is nevertheless similar to Orwell's in its ambition to control every aspect of life: censoring the arts, banishing religion, assigning jobs and spouses, even trying (in vain) to manipulate the weather. Much of its meddling appears in forms that are recognizable as exaggerations of long-standing conservative fears about big government: violent criminals are treated to luxurious rehabilitation in fine country homes; young people are subjected to sterilization; euthanasia centers are mobbed by throngs of the "welfare-weary" who daily present themselves for voluntary annihilation.

Amidst this bleakness we find Miles, the story’s hero who, as both orphan and arsonist, has been doubly favored by a state obsessed with the notion of rehabilitation. Miles’s trouble is that, after enjoying years of the luxuries of prison life, his rehabilitation is abruptly declared complete, and he is therefore forced to enter the grim, gray deprivation of spirit under which the rest of population suffers. He is given work in the euthanasia center, falls for a girl whose face has grown a beard after a botched sterilization, and eventually ends up heartbroken when she leaves for a career as a dancer (her hairy cheeks now replaced by a permanent mask of pink rubber). The government wants Miles, their one bright example of rehabilitative success, to go on a propaganda tour, but he has other ideas, and the story ends with him peering at the flame of his cigarette lighter, entranced by the prospect of the arson he is about to spectacularly commit.

The central problem Waugh is tracing here is one which underlies all his works: that formless, enervating, transmogrifying barbarism he called The Modern Age. In his other stories, the Modern Age is a rude appearance, a rising menace, but in his tale of the future we find it fully realized. Where there were towns now there are Population Areas. Where there were steeples and towers, now there is only the featureless and ill-executed Dome of Security. In place of justice, there is psychology; in place of knowledge, conditioning; and in place of craftsmanship, of all the humanizing pleasures and hardships of making things, there are now only mechanical functions, boredom, futility -- the soul-killing inanity of the modern job. For Waugh, the Modern Age seeks nothing less than the undoing of civilization itself, blindly devouring hard-won consolations and decencies of which it is wholly and unashamedly ignorant.

To feel the shock of that loss is one of the essential reasons to read Waugh, for that great meat-grinding of tradition advanced hugely in his time, and he documents it with biting accuracy and in language so beautifully crafted it stands as a magnificent rebuke to the march of ugliness. That march has, of course, accelerated and gone global in the decades since Waugh, so much that we, surrounded by ugliness of a magnitude he could not have imagined, may at times be blithely oblivious to it. Waugh’s outlining of where that march leads helps us to see it in all its dehumanizing squalor. We who, unlike Waugh, have seen an age of strip malls and plastic cutlery, can’t help but acknowledge the acerbic accuracy of his vision. We may not be lining up at the euthanasia center, but we recognize that much of our world and our work have become so standardized, so shoddy, so hyper-controlled that they are no longer worthy of our love.

What may ring less true for us in this story is what Waugh indicates as the source of the modern scourge. Whereas in his other works the Modern Age is a multifaceted, hydra-headed beast, here the monster is purely a creature of the government. Behind every drab and ghastly appearance of this worthless world there lies a single source: the hubris and confused quasi-humanitarian notions of the state. Emboldened by experts, inflated by theory, the government is driven by an ambition to bring literally everything under its managerial control, and it is that ambition and that alone which has robbed life of its consolation and purpose. Waugh blames the state so vigorously that we even find him straining some notes -- people greeting one another ‘State be with you,’ or criminals presented with a concert and feast after they have dismembered a flock of peacocks. This overemphasis on the state tends to seem oddly off-target to a 21st century audience, to us who, every time we glimpse a box store, certainly feel the curse of a shoddy, over-planned culture, but who do not necessarily feel that curse as an imposition of the government.

Given when Waugh wrote, his fixation on the state is understandable. For him, as for Orwell, the future could be imagined only in light of the double cataclysm of total war which had so radically altered Europe and the world. After the second of those catastrophes -- in which nominally democratic nations massively centralized power and partnered with one totalitarian state in order to defeat another -- the threat of an all-controlling, impersonal government, even in the West, seemed all too real. That possibility only seems remote to us perhaps because over sixty years we’ve seen the rise of other forces -- technology, globalization, financial markets, "the economy" -- whose power is far greater, and whose presence in our lives more pervasive, than that of any state. For a vision that takes into account those forces, we turn to Wall-E.

As bleak as Waugh’s view of the future is, from the opening scenes of Wall-E we know that here we are facing a plight even more dire. The film shows us a completely devastated Earth, devoid not only of all human life, but of all life whatsoever -- not a plant, not a bird, nothing but endless dusty wastes piled with garbage. (An early working title was "Trash Planet.") The sole inhabitant of this ruined world is Wall-E, a robot made for compacting trash, a task he still performs faithfully and pointlessly centuries after the last of his human masters has disappeared.

Wall-E’s lonely routine is interrupted by the arrival of Eva, another robot, who has been sent to Earth to see if its natural systems have recovered enough to produce life. As it turns out, the planet has indeed begun such a recovery, and has produced at least one plant, a young sprout which Wall-E has found and brought to his little hut. Eva takes the plant and, with Wall-E stowed away, returns to her home ship, the Axiom -- a kind of space luxury liner where we at last learn what has become of the final remnant of humanity. BnL (short for Buy-n-Large), a retail mega-corporation which had provided for virtually every human need and desire during the final years on Earth, also provided the Axiom as a means of escape when the planet became uninhabitable. The consumer culture that destroyed the planet finds its apotheosis in the Axiom, its interior an endless series of malls, cinemas, and food stops, through which obese throngs of humanity, their muscles and bones withered from lack of use, glide from pleasure to thoughtless pleasure on what are in effect hovering, high-tech La-Z-Boys.

Wall-E’s lonely routine is interrupted by the arrival of Eva, another robot, who has been sent to Earth to see if its natural systems have recovered enough to produce life. As it turns out, the planet has indeed begun such a recovery, and has produced at least one plant, a young sprout which Wall-E has found and brought to his little hut. Eva takes the plant and, with Wall-E stowed away, returns to her home ship, the Axiom -- a kind of space luxury liner where we at last learn what has become of the final remnant of humanity. BnL (short for Buy-n-Large), a retail mega-corporation which had provided for virtually every human need and desire during the final years on Earth, also provided the Axiom as a means of escape when the planet became uninhabitable. The consumer culture that destroyed the planet finds its apotheosis in the Axiom, its interior an endless series of malls, cinemas, and food stops, through which obese throngs of humanity, their muscles and bones withered from lack of use, glide from pleasure to thoughtless pleasure on what are in effect hovering, high-tech La-Z-Boys.

This remnant of humanity is in no way eagerly awaiting news of Earth’s recovery; with BnL more than ever serving their every wish, they have in fact happily forgotten their abandoned home. Eva, her programming activated by the discovery of the sprout, tries to get the Axiom’s captain to take the ship back to Earth, but is thwarted by a computer auto pilot devoted to the status quo. Only when the captain (who like the other humans has through idleness lost the ability to walk) manages to disable the computer are they able to chart a course home, where the final scene and credit imagery show them learning to grow food and settle the Earth again.

The dystopian vision in Wall-E has two sides: on the one hand there is the image of the Axiom, a human society existing purely for consumerist pleasure, an enclosed simulacrum of civilization that leaves its members stupefied, incompetent, dwindled in soul, forgetful of essential realities. On the other hand there is the Earth: an entity that had once been garden and mother, now only a trash bin and toxic dump. The Axiom would seem to be dystopia enough, but by including the Earth, indeed by beginning with the Earth, Wall-E crucially expands the scope of the dystopian vision. Waugh had shown that the human person shrivels without a nourishing society, but Wall-E goes beyond that insight to reveal an essential linkage: a disordered civilization that does violence to the natural world necessarily does violence to the human person. Where the sacred realities of soil and watershed and air are regarded as commodities or dump sinks, the human soul is regarded as an engine of consumption. There can be pleasures under such a regime; there cannot be goodness.

Wall-E does not shy away from following this recognition to its conclusion: if violence to the earth is dehumanizing, then the consumer capitalist forces which drive that violence are themselves dehumanizing -- in fact, they are the most effectively dehumanizing forces the world has ever seen. But in identifying the consumer capitalism of BnL as the source of our woes, the film does not fall into the dangers of demonizing or simplification. While Waugh’s state seeks control for the sake of control, Wall-E displays a remarkable largeness of mind in portraying BnL as a sincerely benevolent tyrant. There are a few glimpses of its own manipulative ambition to control -- for instance, we see a robot teaching a child “B is for Buy-n-Large, your very best friend” -- but for the most part, the corporation is shown as simply trying to meet the demands of its customers. The portrayal in fact fits what proponents of an unrestrained market say capitalism is: a morally neutral instrument, one that merely expresses, rather than shapes, the will of the consuming public. This characterization so thoroughly plays down the tendency of corporations to manipulate human desire that it may strike many viewers as naïve, but in portraying this benign version of corporate power as the primary agent of our destruction, Wall-E greatly intensifies the strength of its own message. BnL is not, like Waugh’s state, a force that imposes a degraded condition onto us; it is rather a kind of deluded enabler, encouraging -- for its own profit, yes, but for our happiness too -- our instincts of gluttony and sloth and forgetfulness. The vapid blobs of humanity on the Axiom have not been forced onto their La-Z-Boys, but rather have quite willingly chosen, or have at least accepted, that debased state.

Most remarkably, Wall-E manages to implicate us in its dystopian vision while avoiding any hint of finger-wagging. Indeed, in what is perhaps the film’s most surprising touch, we find Wall-E the lonely trash-compactor actually keeping some of the junk he finds -- a light bulb, a Rubik’s cube, a "Hello Dolly" video -- and in his delight over this collection we feel the full difficulty of our conundrum. This stuff is exactly the consumerist garbage that has been the ruin of us, and yet we are undeniably glad to see someone left to enjoy it. It’s junk, but it’s also human, capable of being invested with our affection and memory. The problem we face is a species of gluttony; we all in our various ways have grown to love, understandably, stuff that is nothing less than the killing of our spirit and our world.

In its recognition of the consumerist forces behind our problem, Wall-E is in fact the dystopia that more faithfully represents our predicament; with the benefit of having watched our trajectory for sixty years after Waugh, it is able to produce lines with a truer aim. Limited by his time, Waugh’s vision is consequently too narrow, too focused on the state, too prone to portray us as only victims, rather than agents, of our undoing.

And yet Waugh’s vision offers something indispensable as well; returning to his crucial insight regarding the effect of over-planning and shoddiness on the human character, we see that Wall-E is both a masterpiece and a part of the problem it identifies. For all the poetry of its vision, it is a film literally drawn by computers; it falsifies its ending with cutesiness and a too-easy resolution; it was released, of course, in a blare of marketing, merchandise, tie-ins -- all of the consumerist slop that we ask for and get. There’s none of this accommodation in Waugh, whose story is not only a thing of exquisite craftsmanship, but also of ferocity -- it’s no accident that it ends with the promise of fire. Along with Wall-E’s insights regarding our own implication in the death of our world, we would do well to take on something of the sharpness and intolerance of Waugh’s vision. A world- and soul-killing gluttony is a thing better burned than accommodated.