From Here On: Four Sunday Drives

Part IV: Quaking Aspen

By Don Thompson - Buttonwillow, California, USA - 2 September 2016

For Chris

Smoke insinuates a lawless trash burn,

Smoke insinuates a lawless trash burn,

a mini-Gehenna; or it could be

grass smoldering somewhere in the hills,

a fire we keep an eye on,

nervously. Some years

everything that can burn does.

So desolate here in autumn,

the seared leaves still green

but blotched with raw sienna:

summer, not dead yet, dying

of a slow, debilitating disease.

So dry even our hearts dehydrate,

making us uneasy

about where we’ve been,

about the long, withering seasons behind us

and how close winter is,

no matter how stubbornly the heat persists.

But this old man has outlasted regret

and sluffed off despair, so far,

convinced that a few sips

of love

will sustain us

from here on, inexhaustible,

like the widow’s scant flour and oil,

iuxta verbum Domini…

One Sunday late in October

more than thirty calendar years ago,

you and I climbed

out of our monochromatic valley

to visit a museum

of seasons,

a New England tableau

briefly on display high in the Sierras.

And we brought those colors home,

not the dried leaves

children would have gathered

and soon misplaced,

but an unfaded consciousness

kept vivid until now --

until this inevitable, inward autumn

we’ve come to,

still together, living

in our imagined landscape,

real only in the past, perhaps,

but nevertheless accessible

here on this googled earth:

Zoom in on the new road north,

an overlay on time, fervent

black asphalt with insistent stripes,

yellow that almost convinces us

it will never discolor.

That new highway has a textbook look—

taxes, engineers, and unlimited union labor:

Leviathan at work.

Not the road I remember,

narrow with crumbling shoulders,

infamous for head-ons,

for drunk drivers upended in a culvert;

washed out by flash floods every winter.

And some of its not-quite towns, bypassed

places with names

but no one to call them home,

long dead,

have been resurrected now.

Subdivided, they offer refuge --

a brutal, time-consuming commute,

but worth it:

Not a ghost town, but ghostly

in mid-morning,

curtains on windows like shrouds

so old they’d disintegrate

if it ever occurred to anyone

to open them.

We drove to the end

of its only street and slowly back,

stopping at a clapboard store

to buy snacks. The clerk

said nothing, saw nothing in us --

like the dead looking into a mirror.

But beer stench from the saloon next door

reassured us: Life --

nightlife at least,

or morose locals who drank all day,

keeping themselves in the dark:

In towns like that,

everyone wants out of the light.

The sun at noon could blister ectoplasm

and the moon set fire

to the tinder of a banshee’s hair.

From one end of Main Street

to the other, you see no one,

and nothing moves except the dust

that goes round and round,

practicing the frantic dance

the devil taught it.

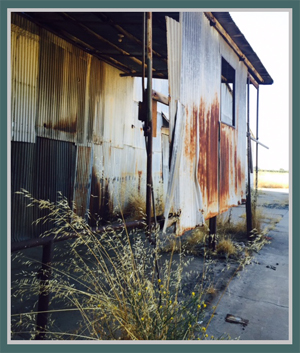

The packing shed had packed it in.

Decrepit, it sat like a huge skull

with its jaw wired

and sheets of warped plywood

nailed over its eyes,

not to keep sensory input out,

but to trap the past --

a bitter ubi sunt

only a few are alive to remember:

In ’37 or so, when Mom

and her family drifted in from Route 66,

she went barefoot to the orange groves,

harvesting the gold

crated and shipped from that shed:

Sierra Sue, Spaniel, Terra Bella.

Oranges are still handpicked

and packed by hand,

some of the same brand names,

though everything is galvanized now,

rustproof -- an illusion,

as if time couldn’t chew through steel

as readily as wood.

The same scattering of battered cars

park on blacktop instead of dirt,

but no one is fooled

by the faux security

of chain-link and guard shacks,

usually unmanned.

The old road east into the Sierras

had a shallow learning curve,

dawdled in tall grass below the foothills

among valley oaks, giants

either so ancient they’d be worshiped

in pagan Europe

or dead for years -- snags

like weathered grave markers

above heaps of rotting branches:

excellent firewood, the best,

but forbidden now by eco-law.

And vanished from Google Earth,

the campground nearby

where I holed up one summer

in a lean year

working too hard at a bonehead job

and driving that deadly highway

home on weekends

to you and our toddler.

Farther up, the pond

that used to be a lake,

high on the dam and glittering:

Rings around the shore

keep a record

of its incremental descent

into emptiness. Drought

and bad luck, of course,

but also the whims

of government have sucked it dry.

Bluegills would take a close look at crickets,

and bass feeling their way

along the bottom

are willing enough to nibble

plastic worms in the murk,

but no one is fishing.

The boat ramp ends in weeds

more than a stone’s throw

above the waterline.

And everywhere, trash bags

spill their guts like roadkill

not even the crows want to touch.

In the dead mountain town, disinterred

now by tourists and commuters,

the abandoned TB sanatorium

has come back to life as condos.

But some residents have heard

coughing in the dark,

though dry and bloodless,

and shivered in cold spots watching

despair condense in their clouded breath.

Others have endured sympathetic night sweats,

ached with phantom pain

from an excised rib,

or felt hopelessness take hold of them

on endless Sunday afternoons.

You and I saw the place boarded up

and the shrubs gone native,

the town itself ignored,

but undaunted;

and a few miles uphill we passed

the inevitable failed homestead:

The gate was chained

with three or four rusted padlocks,

the ruts overgrown that led

to the house and the barn behind it,

both half-finished for fifty years.

The windmill kept turning

above a dry well --

a bad habit never broken.

Who knows whose madness it was

to settle there

or which heir still paid the taxes,

suffering from his own delusions

and clinging to the deed

once held by a loner

who raised wilted, knee-high corn

to feed his gaunt cattle

and fed himself better

on bitterness.

Cor quod novit amaritudinum.

From here, for a few miles, the road

that used to follow the river,

when it could, still does,

accepting terrain too rugged

for engineers to finesse,

and then climbs --

an orange oscillation on the map,

jittery with switchbacks

that look just as wicked from orbit.

That other turbulent river

in which then becomes now

and now dissolves into then,

carries us along like two sticks,

not saturated, not yet,

nor snatched from the current.

But I suspect the whitewater

that elated us so much,

watching it churn over boulders

as if inexhaustible,

has been reduced to a trickle,

tempting vandals with day-glo Krylon

to gloss all that exposed surface,

which, according to their Weltanschauung,

would otherwise be wasted.

Close to the summit, unpaved side roads

crisscross through the woods

among vacation cabins

and the permanent getaways

of misfits with mountain blood,

thin skin, and simple needs,

mostly for a tavern with beer on tap

and some chairs to toss.

And here’s that historic lodge

from which Bonnie checked out,

shot dead by a left-handed proxy

while she slept with her lover

from the rez

who survived his head wound.

All this less than five years

after our visit

on an unhaunted All Hallows’ Eve

before fake blood good enough to fool anyone,

before the license to undress

and the mud lust we live with now.

Aspens wore their bonfire costumes,

a harmless masque rather than bacchanal,

and danced for us

in the muted, andante wind.

That afternoon on the far side of the summit,

we parked and walked for awhile

in lucid air, in exhilarating dazzle,

lumen de lumine --

not merely caught and reflected,

but a source, as if every leaf

contained its own inner light.

Neither of us young, nor naïve,

we took to love as if new to it,

fumbled some intimacies

and held on -- held

to the unlikely idea of us,

almost untenable in this world.

The pines hummed overhead,

incense cedar bowed a cello note,

and faithful dogwood stood by.

Our kisses went on and on

back then, ad infinitum

coming too quickly to an end.

We’ve lived ever since suspended

in that one autumn afternoon,

kept the turning leaves as they were --

gold, citron, copper, burnt orange,

an unchanging anamnesis, no matter

how many actual seasons

have had at us,

with freeze and thaw or relentless heat.

Some would imagine

that those aspens were waiting on the Lord,

the leaves alone together,

each trembling with its own anticipation.

And among them,

as far as earth can offer it,

we found peace that could,

potentially at least,

endure.

And it has.